A colleague recently mentioned to me that he knows a church which hosts a regular fix-it club where broken household items can be brought to be mended. I love this idea – it strikes me as a prophetic stand against the consumerist throw-away culture in which nothing lasts long before it is assigned to the scrap-heap. Indeed, in which this is a basic assumption in the design and manufacture of so many goods.

For me, fixing things is entertainment. Just last week, I spent a delightful day diagnosing the fault in an almost unused, but out-of-warranty, mini-fridge. The switch-mode power supply’s main FET had blown, taking four diodes and the fuse with it. The new components cost £1.26, which is a lot less than the £39.99 retail price for a new fridge. And only a few grams worth of dead electronic components were thrown out.

In the case of the fridge, the manufacturers had been kind. It was easy to disassemble and all I needed were skills, tools and patience (and an acute wariness of high-voltage DC). Many products are deliberately manufactured to be hard to fix. Several months ago, I had to make a special screw-driver to get into a friend’s Kenwood hand mixer.

Once inside, I found the problem was a simple broken wire. Two minutes of soldering turned a useless chunk of rubbish into a productive machine with many years’ life left in it.

We also have a bread machine which is 11 years old. It would long ago have graced a local land fill had I not replaced the transformer and designed and built a new bush for the paddle drive shaft (out of a Teflon sheet from e-bay and much better than the original!)

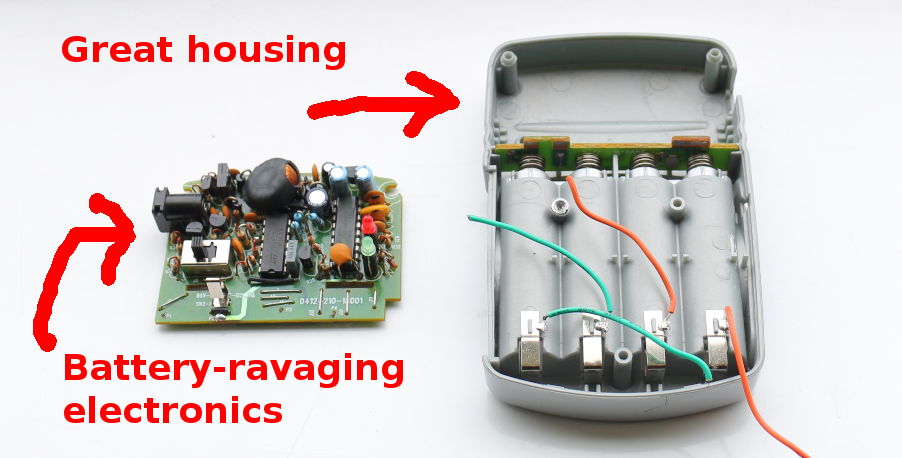

And on it goes. (Presently, I’m pondering how to replace the rubbish electronic components of a bad NiMH charger whose physical housing is, nonetheless, rather good and would be a shame to bin).

Yay me! But the point I wish to make is that I suspect I am in a rather small minority. Most stuff just gets dumped, I suspect, at great cost to the planet. The rate at which we plough through natural resources is shocking. Would it not be good for our society to have a fix-it culture where we expect things to last for well over 10 years and where we fix minor faults rather than throwing away?

The trouble with this idea is that it is not economically financially viable. See how I nearly slipped there? Economically, we desperately need to be more thrifty. We have to reduce our use of resources or run headlong into a brick wall at some point. Economically, not fixing this is what isn’t viable. But financially, with the cost per item of mass-produced automated manufacture being so low compared to the manpower required to find and fix faults, no one could run a successful business fixing things. So we need a new idea. We need an idea based around a non-monetary economy, a volunteer economy, an economy of gift.

Another problem is lack of skills to fix things. Skill comes from practice. With few people practising fixing things, few people will have the skills. And the lack of skill propagates as one deskilled generation fails to pass skills on to the next. So we need a deliberate effort both to pass skills on and to practise them.

Even so, fixing things is not for everyone. Not everyone has the aptitude or interest to learn the skills. For me, fixing things is fun. For many people it would be a drudge or, even, terrifying. Well, that’s okay. Let those without the aptitude bring their broken things to those of us who can fix things.

But how might they find us? A while back, I thought the answer might be to offer my fix-it ability through Streetbank. Indeed, I still think this, but despite having offered months ago, no one has taken me up on my offer. Probably there is a side-conversation to be had here about how not all neighbourhoods have caught the Streetbank bug.

Whatever the case, the church-based “fix-it club” idea has to be at least as good as Streetbank for socialising the concept of a fix-it society. (And, in any case, can function alongside Streetbank advertising). The fix-it club also solves the skills problem. Bring together people who are interested and have aptitude and they can (and naturally will) share their skills. As a teenager, I’d have loved to be a member of such a club – and would have learned much. Finally, clubs by their very nature being voluntary and generally non-profit, a fix-it club is an excellent example of non-monetary economy at work.

What could be better than a club which allows skills to be shared, offers a valuable resource to society, saves the planet and is jolly good fun?